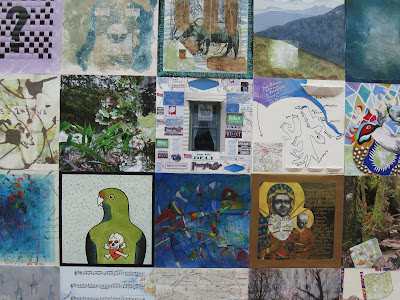

In the Autumn of 2008, Unity College organized a program called The Art of Stewardship. We brought fifty artists, scientists, and sustainability activists to campus. We asked them to envision the college as a campus canvas for environmental art. They presented us with ideas including mandala sand paintings, murals on the sides of buildings, recycled materials art sculptures, soundscape designs, native plants sculptures, an arrow of time to represent geological events, and landscape artwork that captures the movement of water, grass, and pollen.

These projects ideas can be constructed at minimal expense, while providing local and regional artists with a venue to display their work. They also represent terrific opportunities to get students, staff, and faculty engaged in taking great pride in the campus, as well as making the landscape much more interesting.

There is also a deeper cognitive advantage. At the core of understanding sustainability, biodiversity, and climate change is a perceptual challenge. Art projects use imagination to convey scale. They are a bridge to scientific understanding. Further, art projects catalyze some of the emotional responses surrounding these issues, from despair and grief to wonder, celebration and gratitude. Ultimately, this kind of collaborative art allows the campus to experience reciprocity between the built environment and the natural world.

Sustainability should entail aesthetics every step along the way. The people who live in a place should have the opportunity to make it their own through ephemeral and permanent artistic installations. This has the great virtue of making a campus a more vital and dynamic place. Even better, every art project contributes to the sense that the campus is a place in space and time, a living and working environment that creates an aesthetic mark in the bioregion.

Now it’s Your Turn

These nine elements are part of my own emerging narrative, both as a sustainability explorer and a college president. Hopefully, they provide you with a template of ideas for your campus, adapted to your roles and responsibilities. I hope that you will find your own sustainability narrative, that you will come up with an entirely new catalog of ideas and possibilities, and you will realize that these initiatives are crucial to your educational position and your planetary citizenship. When you come up with a great idea, and you’ve accomplished something really neat, send me a note and tell me what you’ve done. Maybe it’s something I can write about in a future essay, or include in my own work, or I can pass on to someone else who will find it helpful.